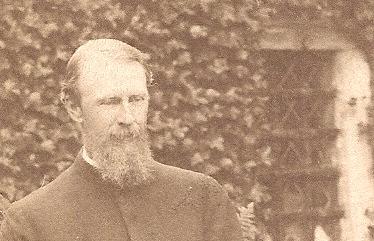

REVEREND EUSTACE WILBERFORCE JACOB

Born 17th February 1835 - Died 9th July 1871

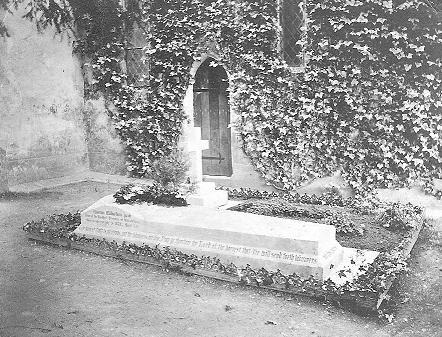

He was the second son of Philip Jacob, Archdeacon of Winchester, born 17th February 1835, baptized 5th April 1835, died without issue 9th July 1871, and buried at Crawley 14th July 1871. He was named in part after Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Winchester, a good friend of Philip's, and son of William Wilberforce.

Fortunately some letters written by and to him have survived; they give us an insight into his life.

His nick-name was Enty. He would appear to have lived a distburbed

life. An extraordinary letter written to his father in 1846 from school demonstrates

his lack of confidence: I had not written before as I felt you would not

have time to read my letter. I have written to Mama several times. I have

had a sort of horrid

confused nightmare with something about home that makes me almost believe

that they will come true. I will give you an instance of the rubbish last

night. I fancied that I went home and found Gertrude (his sister) dead of

the complaint called Zabia or Complaisance or some meaning like it. I forget

when people have it..... it was almost a speedy death... will you try to spare

time to write me a few lines..... your affectionate son. He did not enjoy

his time at school.

On 6th July 1855 he had joined the army as an Ensign. In a letter to his father from Chatham barracks, dated December 1855, he lists accounts; he was almost certainly being financially supported by him. I have just come off guard this morning. I went round the sentries in the Dockyard at half past one at night, the wind blowing as cold as ice. I kept my cloak over my chaco and walked as hard as I could with the Sergeant who accompanied me as usual with a lantern. Without the aid of a light one might tumble into the Thames, or break ones neck over chains and timber. When I got back I threw off my tunic, and trousers, put down the gas light a little, and rolled myself up on the couch in cloak and railway rug, passing a bad night and waking with a splitting headache, the usual effects of bad wine in the evening and gas in ones bed room.

Writing to his brother Augustus on 3rd February 1857 he says I got a step lately that cost me £7/10/0 and made me third ensign. I hope to be second very shortly, as a Lieutenant wants to leave the service, and has offered to go for £250 over Regulation. On his way to Crawley from Cork he stopped off at London for two nights. The Archbishop (of Canterbury) offered a clerkship in the British Museum, and he called on Mr Panizzi there who was the chief librarian to make enquiries about the post. He declined it as being in many ways worse than the army because, though the pay began at £130, it never got beyond £200 a year, with no retiring pension, whereas in the Army he would receive one after 30 years service. I went into Winchester some days ago and dined with cousin Edward (Edward Long Jacob). He, like others in the family, although never in serious money difficulties, did have what we might call their cash flow problems. Money, or the lack of sufficient of it, was forever an issue. There was always the prospect of a legacy, and a number of these were received. Writing from Cork Barracks, Ireland. in 1857 to his brother Augustus, the matter of a legacy left by Edward Legrand was raised, where there appears to have been some dispute.

On 21st September 1858, writing to his father, he describes steaming away to Spithead, with the band dressed in their blue uniforms playing 'Auld Lang Syne' and 'Rule Britannia'. He was sailing for Calcutta. A letter from his sister Isabel dated 10th September 1858 stated he was due to sail in the Lady Jocelyn on the 18th. We see in the Bombay times that uncle George has been made Brigadier General. A letter from John (John Jacob a cousin) says he is most uncomfortable. You know he has lately changed his regiment and is very sorry he has done so now, as the officers are a bad set. He is in the same regiment as Adolphus Jacob (another cousin). He writes a lengthy letter from aboard the Lady Jocelyn describing much of his journey bound for the Cape.

However, an army career was obviously not for him. He had spent his time in the army in the 99th (Lanarkshire) Regiment of Foot, being made Lieutenant on 24th November 1857, and attaining the rank of Captain, by purchase from Thomas Hollingworth Clarkson, on 4th January 1861. He was still in the army in 1862 when the New Army List was published, but must have left in that year or in 1863. In 1863 a book he had edited appeared, ' Something New; or, Tales for the Times'. being short stories contributed by a numer of writers. It was published in London by Emily Faithful, Printer and Publisher to Her Majesty, where he was described as (late) Captain of 99th Regiment.

For a period he was at a loss at what path to take, but eventually decided upon the priesthood. He had in the past displayed a certain missionary zeal and decided to go to Natal, South Africa, a British Colony, where his father and his brother Edgar had built up contacts. He was there in 1866, his address being Karkloof, Pietmaritzburg, Natal.

Writing from Maritzburg, Natal, to his father, we see that he was ordained priest on Sunday 18th December 1870. This apparently did not happen without some controversy. One of the examiners was dissatisfied with both Mr Rolfe and myself... but the Dean's letter only reached the Bishop at about noon on Saturday and caused him a good deal of anxiety, as both Rolfe and myself said that if the Dean could not take part willingly in our ordination, we were quite prepared to return home as Deacons..... He asked where his papers were at fault. The Dean said he gave a poor analysis of the office of the holy Communion. The letter goes into theological details. Writing to his brother Edgar on 17th December he complained about the obstacles the Dean had thrown in his way. The Dean had demanded that he and his friend Rolfe should give an absolute pledge to remain in the diocese and devote themselve to study for 2 years. He declined in his presence but stated that if it eased his conscience he would not apply to him to sign his testimonials should these be required. He firmly believed the Dean had a dislike for literates. His friend Rolfe was not on the most friendly terms with the Dean, as Mrs Rolfe had a ladies school and Alice Green, the dean's daughter, was expelled from it a short time before for some misconduct. He was however ordained.

Whilst in Natal he had raised funds for the building of churches. His church was that of Howick, which he owned.

He had the new church built. He thanks his brother Edgar for speedily raising £50. He had a salary of £80 a year, out of which he could not pay for the church, the costs already being £81 and rising. He would have to consecrate the church without it being paid for. It cost him £63 last year alone, and that out of his own pocket. He was, however, generous in the assistance he gave to others. He subscribed £12 to schools in the district, two of the schoolmasters being half starved there being no government grant, and they wholly dependent upon the school fees, which were irregularly paid in cash and kind. The clergy in Natal were acording to him in abject poverty, totally dependent on true Christians in England. He heard Bishop Colenzo had £600 to spare, and as he had heard he was coming to visit him, on his arrival he asked him for a loan of £80. The Bishop was prepared to lend him £60, but Eustace took only £30, feeling that he could more readily repay the lower sum.

He writes again about the very bad state of affairs in Natal. There was no money, even a graduate cannot be got for the church school. Another major complaint was with SPCK. They were not assisitng the church in Natal with church books. Bishop Macroie, when he came to England, and where he met up with Philip and his family, stated that he tought he had come to a country that held the Catholic faith. The Church of England to him had lost all interest in Colonial churches. He attributed this in part to them paying too much attention to their pet diocese - New Zealand. Those who love Christ, love his poor, and who so poor as the untaught savages, Eustace writes.

His health by this time was not good and he stated he was returning to England to recover. We do not know what he died of, but by his own admission he was often very short of breath, gasping for air.

Writing to his sister Gertrude on 29th Aprill 1869 he expressed his fondness for Edda, whose family came from Natal, and as far as I can see she was originally invited to stay with the family as a companion to Edith. She was, in Eustace's opinion, the general favourite out of the family of 14. She had an elder sister called Issy, who at the time was a governess in the house of the family of a Mr Osborn, a magistrate at Newcastle. At one time it was thought she too might come and live with Philip's family. Both Issy and Edda had run a ladies school in Pietzmaritzburg at one time. Edda is described as a thin, pale lass, of 5' 6" in height, with large dark soft eyes and raven hair, of Spanish rather than Irish descent. If we can get photographs on the coast of our two beautiful selves we will send them to you, he goes on to say in the letter. He married Edwardine Fannin (Edda), but they had no issue. Edda, on Eustace's return to England, joined Philip's household, where she remained for about three years.

Edda was not originally liked by all members of the family.

Gertrude for one found her somewhat irritating. Writing to Edgar after her

and Eustace's return from Natal she offers a frank assessment:

As you are going home after Easter you will be able to judge for yourself

about Edda. She is (this meanwhile) very graceful and quiet, exceedingly shy

at first and during this she has a startling way of fixing her large brown

eyes at you and an uncomfortable manner of holding her mouth, but you will

probably find her quite at home and see none of this. She hates Enty's writing

in the papers and says it has done him such harm and that all her people looked

to her to stop him, and has found herself only as a fly on the wall. Then

she thought a baby might divert him, but no baby came! The truth is, he (Eustace)

has neither the intellectual capacity nor temper, this chiefly, for Natal

where religious controversy is already I suppose more bitter than anywhere

else, and I earnestly hope he will not go back. It would be better also for

Edda not to be related to 2/3 of the parish. She is exceedingly nice

and right feeling in all things and thinks a great deal of her hubby. She

makes out a much more cheerful account of their life since their marriage

and says naively that she thinks Enty put down when he had a bad dinner only.

He always had two eggs for dinner and the same for tea and mutton (4d a lb)

for dinner. She can't eat eggs and if any body was starved it was her. She

is almost to be

the

man of Turin

who was so exceedingly thin

so that by a mistake

he got mixed in a cake

so they baked that young man of Turin.

After Enty's death there was the problem of what to do with Edda. Gertrude writing on 12th December 1873 to her brother Edgar. One was trying to induce her to return to Natal. She writes: Edith has written to me again lately about Edda and her future. Bishop Calloway's return to Natal (no time I believe yet fixed) seems to make so good an opportunity for her to rejoin her people, if she can be induced to do so. It is a difficult question and one not easy to move in. I will try and state the different points of view. She is better in health and spirits at her ease in company and able (now in the Close) to entertain visitors nicely. She is improved in every way, but the natural defects of her constitution (of mind and body – it suits my meaning better than character) now become more apparent as we see what training and education fail to do. Briefly she will never be much good unless she marries again and this gives her creeper in the nature a pillar of support. If she remains in England this is very unlikely. If she returns to Natal with her newly refined manners etc she will probably do so and secondly the extremely quiet Crawley life is not suited to her. She is a depression on Edith and a care and an anxiety. But Edda will never move herself unless influenced from without. She says to Edith and to Crawley and while I believe she feels at the bottom of her soul her own failings, it has only the effect of depressing her almost to the point of melancholymania and I do not think she feels at all what some would do keenly her entire dependence on her husbands family a burden. She cannot make any plans for herself, no seaweed torn from its rock is more helpless. Her own family naturally feel a delicacy in seeing her to come away from a life of much greater comfort, but Mrs Methley has written some time ago saying that when she did come she must live with her as she had no children. She will have been three years in England next March and if she were to return it would be better for her to do so whilst she is still young and before she gets too accustomed to this English life to be able to bear the colonial. The money part of the question must also be thought of. At present Edith allows her £50 a year for clothes and pocket money, Pater keeping her, paying laundress and not as a rule, but almost always, her journey money. Now if she were to return he might give her £50 a year for his life, or until she marries again. The money raised by the sale of Howith furniture £50 is in uncle’s hands and he is adding interest at the rate of 10% to it and will do so until it reaches a hundred, so this is a little nestegg for her Fannier (or Fannin?) family....

Source:

.jpg)